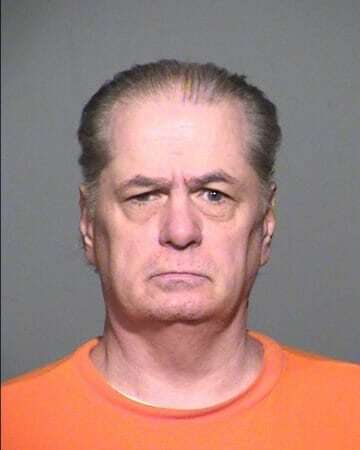

Barry Jones was sentenced to death by the State of Arizona for the sexual assault and murder of a four year old girl. According to court documents Barry Jones sexually assaulted and abused the four year old girl. Jones would not allow the mother of the child to get medical attention. The next day the child was brought to the hospital where she died from internal injuries. Barry Jones was arrested, convicted and sentenced to death.

Barry Jones 2021 Information

ASPC Florence, Central Unit

PO Box 8200

BARRY L. JONES 114690

Florence, AZ 85132

United States

Barry Jones More News

The State charged Jones with sexual assault, three counts of child abuse, and the murder of Rachel Gray, age 4. In April 1994, Rachel’s mother and her three children were living with Jones. On the afternoon of May 1, 1994, while she was asleep, Jones took Rachel out of the house in his van, and was later seen hitting her with his hand and elbow. When the mother awoke, she discovered that Rachel’s head was cut and she was bleeding. Jones said that Rachel cut her head when some neighbor children pushed her down. Rachel continued to bleed and throw up during the night, but Jones would not let Angela take her to the hospital. By the time Rachel was taken to the hospital, she was dead as the result of a ruptured intestine. The jurors found Jones guilty of all five counts. In addition to the sentence of death for the murder, the trial court sentenced Jones to concurrent sentences totaling 35 years for the first three counts, and a consecutive sentence of life with no parole eligibility for 35 years for the fourth count.

Barry Jones Other News

ON A CLEAR, blue day in late spring, Arizona Assistant Attorney General Myles Braccio stood before a three-judge panel of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. It was just after 10 a.m. Braccio had a half-hour to salvage a 24-year-old death penalty conviction that had been overturned by a federal judge. “Your honors,” he began, “this case today presents nothing more than a habeas petitioner who hired several new experts, many years after his convictions and sentences, in an attempt to undermine the jury’s verdicts.”

The petitioner was Barry Lee Jones, sent to death row in 1995 for an unspeakable crime: the rape and murder of a 4-year-old girl. Jones had always sworn he was innocent — and the experts in question, hired by the Office of the Arizona Federal Public Defender, had dismantled the case against him. During a seven-day evidentiary hearing held in 2017, witnesses had explained in sobering detail why the state’s medical theory of the crime was impossible. Had Jones’s trial lawyers presented such evidence, U.S. District Judge Timothy Burgess ruled in July 2018, “there is a reasonable probability that his jury would not have convicted him of any of the crimes” that sent him to death row.

Burgess ordered Arizona to swiftly retry or release Jones. Instead, the state appealed to the 9th Circuit. An oral argument was scheduled for June 20 at its headquarters in downtown San Francisco. The courthouse at Seventh and Mission looks stately but plain from the outside, but inside it is startlingly magnificent: an opulent Beaux Arts building replete with marble, vaulted ceilings and a bronze elevator cage, just past security. Braccio, 39, arrived unaccompanied by his colleagues with the Arizona Attorney General’s Office. With a new beard, mustache, and glasses, he was now the face of the state’s determination to execute Jones.

Jones’s actual innocence was not up for debate. Rather, the judges had to decide whether they agreed with Burgess that the new medical evidence would likely have led to an acquittal if considered by a jury. They also had to address a more vexing legal argument advanced by the state: that under the sweeping Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, or AEDPA, Burgess should not have granted the 2017 evidentiary hearing in the first place.

The state’s position seemed weak, if not desperate, on the one hand. The case against Jones had been so thoroughly discredited that it was hard to imagine how the remaining evidence against him could survive the scrutiny of a new trial. Of course, from the state’s perspective, that was the point of appealing. Arizona prosecutors clearly believed it would be easier to convince a panel of federal judges that Burgess was wrong on the law than it would be to convince a jury to reconvict Jones. At this stage of capital appellate litigation, cases are most often won or lost on procedural technicalities, no matter how clear cut the underlying facts may seem.

Braccio began by recasting the medical testimony at the 2017 evidentiary hearing. The evidence was actually “double-edged,” he argued. Even if it did not fully support the original theory of the crime, it still supported other elements of the state’s case. And those were enough to reinstate Jones’s conviction and sentence.

The judges looked skeptical. They had reviewed the voluminous records in the case. The files dated back to the morning of May 2, 1994: the day 4-year-old Rachel Gray arrived at a Tucson hospital, lifeless, bruised, and showing injuries to her head and vagina. She and her siblings had been living with their mother, Angela Gray — Jones’s girlfriend at the time — in Jones’s cramped home at the Desert Vista Trailer Park. An autopsy would show that Rachel died from a blow to her abdomen that ruptured her duodenum, part of her small intestine, leading to a deadly condition called peritonitis. There was little doubt someone had violently harmed the child. But the lead detective never investigated the timing of Rachel’s fatal injury, merely assuming it had been inflicted on the eve of her death. Law enforcement immediately seized on Jones, ignoring any alternative suspects.

In his ruling overturning the conviction, Burgess called this a “rush to judgment.” The state had placed its entire theory of the crime within a narrow window on May 1 — during which Jones had been seen with Rachel taking short trips in his van — but now it was clear that Rachel’s condition could never have become so grave so fast. The timeline used to convict Jones no longer fit, 9th Circuit Judge Richard Clifton told Braccio. “We’re close to the OJ anniversary,” he added, “and things don’t fit, you gotta acquit, right?”

In a judicial circuit famed for being the most liberal in the country, Clifton, 68, is among the more conservative members of the bench. Seated next to him was another judge who is no bleeding heart: Judge Johnnie Rawlinson, a former prosecutor from Nevada. The third and most liberal member of the panel was Judge Paul Watford, appointed by Barack Obama. Ideologically, it was a mixed bag. But if there were any deep disagreements over the case, they were hard to discern.

The stakes were high for Jones going into the oral argument. But they would soon become even higher. In July, U.S. Attorney General William Barr announced plans to resume federal executions — and Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich immediately signaled plans do the same. “As you know, Arizona has not carried out an execution since 2014,” he wrote in a letter to Gov. Doug Ducey. Under a legal settlement following a notorious botched execution, Arizona had adopted a new one-drug protocol allowing for pentobarbital — the same drug just chosen by the Justice Department. “This suggests that the federal government has successfully obtained pentobarbital,” Brnovich wrote, noting that Arizona had struggled to acquire the drug. He asked for the governor’s help finding a supply to restart executions. “Justice must be done for the victims of these heinous crimes and their families. Those who committed the ultimate crime deserve the ultimate punishment.”

There is no question that the original charges against Jones were some of the worst crimes imaginable. But the oral argument made clear that Arizona is now trying win back Jones’s death sentence on any possible basis — even one that radically alters the original theory of the case.

Jurors found Jones guilty on four counts along with first-degree murder: three counts of child abuse and one of “sexual assault of a minor under fifteen.” Under Arizona’s felony murder law — in which a person can be found guilty of first-degree murder if a death occurs during the commission of a felony — any of the four counts were sufficient to support a death sentence. To reinstate Jones’s conviction, Braccio just needed to convince the panel that a jury would still convict Jones on any one of the original counts.

The judges swiftly shut down Braccio’s first line of argument: that despite all the new medical evidence, a jury would still have convicted Jones of sexual assault. This was a somewhat baffling place to begin; of the original charges against Jones, it was perhaps the weakest. There was never any physical evidence tying Jones to Rachel’s vaginal injury. A pediatric pathologist had found that, while there was evidence of re-injury, the original wound dated back weeks — possibly before Rachel lived with Jones. Braccio’s claim didn’t stand up, Clifton told him. “Because once you open the door to an earlier time period, you open the door to lots of other potential culprits.”

Braccio moved on to his next argument: Even if a jury would not have found Jones guilty of physically assaulting Rachel, he said, it would definitely have convicted him on a separate count of child abuse: the failure to take Rachel to the hospital the night before she died.

This argument was harder to dismiss. It was true that Rachel was visibly sick and injured that evening. As Braccio pointed out, multiple neighbors had expressed concern — and one of Jones’s own medical experts had testified that it would have been apparent to anyone that the child was unwell, even if the reason was unclear. Particularly damning for Jones was that he had admitted to lying to Angela Gray about taking Rachel to get medical attention earlier that day. As Jones would tell police, Rachel had bloodied her head after falling from his parked van; she said a little boy had pushed her. Jones said he was taking Rachel to be seen by paramedics at a nearby fire station but changed his mind after spotting a police car. Wishing to avoid being caught with a suspended license, Jones said he drove to a Quik Mart, where an EMT shined a light in Rachel’s eyes and concluded that she was OK. “He said something about her, her eyes being reactive equal, reacting equal, something,” Jones told police.

The head injury was not what killed Rachel. But the lie about taking Rachel to the fire station made Jones an early suspect. However, as Jones’s lawyer, Assistant Federal Public Defender Cary Sandman, argued, it was Gray — known to be physically abusive toward her kids — who did not want to take Rachel to the hospital that night. She was afraid she would be suspected of child abuse. In fact, Pima County prosecutors had tried and failed to win a felony murder conviction against Gray on the same charge in 1995. She was given eight years instead.

But most importantly, Sandman said, the jurors who convicted Jones of “intentionally and knowingly” denying medical care to Rachel had been persuaded that he committed the underlying offenses — namely raping and fatally beating her. In her closing statement at trial, the prosecutor said that Jones had deliberately refused to take Rachel to the hospital in order to cover up his deadly actions. This argument was inextricable from the jury’s decision to find Jones guilty on all counts, Sandman argued. “I think that the conviction has to be set aside,” he told the judges. If the state decides to retry Jones — a decision the attorney general’s office has repeatedly tried to avoid — “they can retry him on that count.”

Braccio vehemently disagreed. Jurors had been instructed to consider each count separately, he pointed out. He asked the judges to simply discard the horrific charges at the heart of the state’s original case and fast-forward to the part where Jones did not take Rachel to the hospital. “I think you can look at the evidence from trial in this case and start exactly when he returned to the trailer park with Rachel after these numerous trips he took,” Braccio said. “Subtract everything else — everything else that happened before that. And the record is overwhelming to convict him of fatal neglect in this case.”

Watford pushed back. “You’re now asking us to hypothesize an entirely different trial that never occurred,” he told Braccio. But the judge was more incredulous at a different claim peddled by Braccio: that under Arizona law, it did not matter whether Jones even realized Rachel was gravely injured on the night before she died. His failure to take her to the hospital still made him guilty of murder.

“That’s a pretty tough standard to apply a death penalty to,” Clifton remarked. Never mind the death penalty, Watford said. Was Braccio really suggesting that a parent who fails to take their kid to the hospital can be convicted of murder — even if they have no idea their child’s life is at risk? “Absolutely correct, your honor,” Braccio said.

“I can tell you the Eighth Amendment does not permit someone to get the death penalty for doing that,” Watford responded. “That has got to be true. Correct?” Braccio demurred. But taken to its logical conclusion, that’s exactly what he was saying.

It has been more than a year since Jones first heard the news of his overturned conviction. The order last summer brought a palpable sense of excitement and relief that seemed to mark the end of a very long road. But the state soon made clear it was not giving up, and despite Burgess’s order telling Arizona to retry or release him, Jones was not likely to go home anytime soon after all.

With a ruling from the 9th Circuit panel not likely to come until the end of this year, the next few months will extend what has already felt like an endless series of waits for Jones. It had taken eight months after the 2017 evidentiary hearing for Burgess to overturn his conviction. Before that, it was a lengthy wait for the hearing itself — not to mention the years it took his lawyers to win the hearing to begin with. Even if the 9th Circuit rules in Jones’s favor, there is no reason to believe the state will yield.

I first wrote about Jones in the days leading up to the 2017 hearing. The records, police reports, and trial transcripts were filled with red flags pointing to a wrongful conviction, from prosecutorial misconduct to junk science. Two jurors who voted to find Jones guilty had since expressed misgivings about the case. And friends and neighbors who knew Jones from Desert Vista told me that they never believed he was responsible for Rachel’s death.

In the meantime, there have been significant shifts in Arizona where the death penalty is concerned. The same year as Jones’s evidentiary hearing, several former prosecutors and judges threw their support behind a petition before the U.S. Supreme Court, brought by a man on death row named Abel Daniel Hidalgo, who argued that Arizona’s death penalty was so overly broad as to be unconstitutional. Hidalgo’s attorneys presented statistical data that showed 98 percent of first-degree murder defendants in Maricopa County (where the death penalty is most frequently sought) were eligible for the death penalty. This flew in the face of the notion that capital punishment be reserved only for the most egregious cases — for defendants who are the “worst of the worst.”