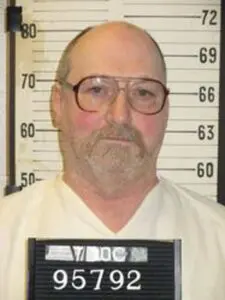

David Miller was executed by the State of Tennessee for beating to death a woman. According to court documents David Miller invited over Lee Standifer to a home where he was staying and would proceed to beat to death the woman. David Miller would be executed by way of the electric chair on December 6, 2018

David Miller More News

Death row inmate David Earl Miller was pronounced dead at 7:25 p.m. CST on Thursday after Tennessee prison officials electrocuted him with the electric chair. He was 61.

He is the third person executed this year and was the longest-serving inmate on Tennessee’s death row.

Miller was sentenced to death for the May 1981 murder of 23-year-old Lee Standifer of Knoxville, who was mentally disabled.

Miller brought her to a pastor’s home where he was staying and struck her across the face with a fire poker.

He hit her with enough force to fracture her skull, burst one of her eye sockets and leave imprints on the bone. He stabbed her over and over — in the neck, in the chest, in the stomach and in the mouth

The winter sky above Riverbend Maximum Security Institution turned dark early with threats of rain later in the evening. Mounted horse patrols circled the prison parking lot as a small number of people on both sides of the death penalty debate stood in the cold.

Media witnesses entered the building and waited in front of a large window that looked into the execution chamber where, on the other side of the glass, Miller sat pinned in the electric chair.

No one from Standifer’s family came to witness the death.

With no emotion in his voice, Miller said his last words but at first could not be understood. The warden asked to him to repeat himself.

With “Beats being on death row,” the execution began.

An expressionless Miller stared ahead as he was held down by buckles and straps. His cream colored pants were rolled up and electrodes were fastened to his feet.

His fingernails and toenails were untrimmed. Cuts were seen on his legs.

Prison staff placed a large wet sponge soaked in saline solution and a metal helmet on his shaved head. Solution dripped down his face and chest.

One of the prison staff wiped Miller’s face with a towel.

A black shroud was placed over his head.

The warden gave the signal to proceed.

At 7:16, the first jolt of 1,750 volts of electricity was sent through Miller’s body. Witnesses could see him stiffen and his upper body raise up on the chair.

It was quiet. He made no sound but his hands were in fists and his pinkies stuck out over the arm rest of the seat.

After he lowered on the chair, he wasn’t seen moving again.

A second jolt was administered for 15 seconds.

The doctor overseeing the death checked on Miller’s vitals.

He was dead. The curtain came down.

“Miller cleared” came over the speakers.

The execution occurred similarly to Edmund Zagorski’s electrocution a month prior. Down to the clenched fists, strained pinkies and no signs of breathing after the first jolt of electricity.

Media spoke with Standifer’s mother on the phone. She said her daughter lived a life of love, of passion and ultimately her family didn’t want Miller to ever be out on the street again.

After Miller’s death, his attorney Stephen Kissinger spokes at a press conference. He said Miller “cared deeply” for Standifer.

“…she would be alive today if it weren’t for a sadistic stepfather and a mother who violated every trust that a son should have,” Kissinger said. “…Maybe what I should be doing is ask you all that question. What is it we did here today?”

Kissinger said Miller was “a friend, a father and a grandfather.” During their last conversations, Miller said he had the opportunity he had to make “just a handful of close friends.”

“He mentioned Nick, and Gary and Leonard. And if those guys get a chance to hear this, I want them to know that they were with him until the end,” Kissinger said.

“In the state of Tennessee, we reserve the ultimate and irrevocable penalty of death only for the most heinous of crimes. Lee Standifer was a special needs woman living a full and productive life,” Lt. Gov. Randy McNally, R-Oak Ridge, said in a statement.

“That life was taken in a cruel, savage and torturous fashion by the individual put to death tonight. Justice, long delayed, has now been served. It is my solemn hope the family of Lee Standifer can now be at peace.”

Miller’s death came with less legal wrangling than the two death row inmates who were executed before him earlier this year.

Billy Ray Irick’s execution by lethal injection on Aug. 9 and Edmund Zagorski’s execution by electric chair on Nov. 1, in a way, set the tone for Miller’s case.

Irick’s execution took at least 20 minutes to complete and his attorneys argued it came with great pain.

Months later, Zagorski chose the electric chair after a legal challenge to Tennessee’s three-drug lethal injection protocol failed. He believed death by electrocution would be quicker and less painful, but maintained that both methods are unconstitutional.

Miller was one of four death row inmates to file suit in November, arguing that a firing squad would be more humane than either of the state’s two execution methods.

But Tennessee law does not allow a firing squad execution.

A federal appeals court blocked an attempt to delay Miller’s execution while he challenged the constitutionality of lethal injection and the electric chair

In an opinion handed down Monday, the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the federal district court in Nashville. In order to secure a stay of execution, the appellate judges wrote, Miller would have to show he was likely to succeed in challenging the state’s methods are cruel and unusual.

A majority of the judges said he had failed to do so.

Miller’s attorneys appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which also rejected his efforts. But Justice Sonya Sotomayor dissented.

“Tennessee is scheduled to electrocute David Miller tonight. Miller is the second inmate in just over a month who has chosen to die by the electric chair in order to avoid the State’s current lethal injection protocol.” Sotomayor wrote in her dissent.

“Both so chose even though electrocution can be a dreadful way to die. They did so against the backdrop of credible scientific evidence that lethal injection as currently practiced in Tennessee may well be even worse.”

It’s still not known how Miller entered Standifer’s life. But there are guesses.

She was naive and trusting. Almost innocent like a child.

He was handsome. They were the same age.

Those who knew Standifer said she never turned down a chance to make a new friend.

On May 30, she called her mom around 5:30 p.m. and walked out the door at 7 p.m. to meet Miller.

Police later retraced their steps: from the YWCA to the Hideaway Lounge, a favorite hangout of Miller’s, now torn down; to the library on Church Avenue, where he checked out a book that included descriptions of murder during sex; and to the bus station, where Miller finagled a taxi ride to the pastor’s home in South Knoxville.

It was just after 9:30 p.m. when the cab dropped them off. It was a Wednesday night, a common day for church prayer meetings so the pastor was away. The pair had the house to themselves.

Miller later told police that Standifer, whom he’d given alcohol, grabbed him and sent him into a blind rage when he told her he was leaving town.

An autopsy report determined he struck her with a fire poker and then stabbed her repeatedly. Some of the wounds went so deep — piercing bone — they could only have been made by driving the knife with a hammer, the autopsy found.

“I turned around and hit her,” Miller said in a taped confession. The blood “just sprayed all over when I hit her. … She quit breathing. … (I) drug her downstairs through the basement and out through the yard and pulled her over into the woods.”

The pastor came home from church and saw the carpet soaked with blood. Miller told him got a bloody nose in a bar fight. The pastor ordered him out but gave him until the next day.

In the morning, he drove Miller to a truck stop and gave him $25. When the pastor returned home, his headlights caught the outline of Miller’s bloody shirt hanging in the street and Standifer’s body underneath.

Miller lasted only a week before authorities in Columbus, Ohio caught up to him and arrested him when he tried to pay a bar tab with a counterfeit $10.

At first, he tried to deny he had murdered Standifer. But soon, he realized he was “a caught rat.”

Miller’s attorneys have argued he lashed out in a burst of psychotic fury, driven by years of pent-up anger from a lifetime of abuse.

Miller was born in July 1957 near Toledo, Ohio. He was the product of a one-night stand in a bar. His mother drank throughout her pregnancy and was later diagnosed with brain damage from exposure to toxic fumes at her job in a plastics plant.

He was 10 months old when his mother got remarried to an alcoholic who routinely beat him with boards, slammed him into walls and dragged him around the house by the hair, according to court records.

Miller told social workers he had his first sexual experiences when abused by a female cousin at age 5, by a friend of his grandfather’s at age 12 and by his drunken mother at age 15. His family disputes this account.

Miller tried to hang himself at age 6 and began drinking, smoking marijuana and huffing gasoline daily by age 10. By age 13, he’d landed in a state reform school where counselors regularly whipped boys with rubber hoses and turned a blind eye to sexual molestation.

He later said he couldn’t remember a single person from his early years ever telling him they loved him.

“Being beaten by his stepfather is the earliest memory that Mr. Miller can recall, and beatings are the rhythm of his childhood,” a clinical psychologist wrote after a court-ordered examination. “Mr. Miller, from a very early age, harbored a simmering rage.”

Miller joined the Marine Corps in 1974 at 17 and made it through boot camp but deserted when he learned he wouldn’t be sent overseas to fight in Vietnam. He came home to Ohio, got a girlfriend pregnant, and left again when she chose to marry another man and raise their child, a daughter, without him.

He bounced between Ohio and Texas, working odd jobs as a welder and bartender. He was hitchhiking through East Tennessee when a car driven by the Rev. Benjamin Calvin Thomas stopped on the shoulder of Interstate 75.

He invited Miller to stay at his home.

Twice officers arrested Miller on charges of rape. Each time the women failed to press charges, saying they were scared of Miller, and the charge was dismissed.

Defense lawyers argued Miller was venting the rage he still harbored at his mother. Prosecutors said he was working up the nerve for the crime that followed.

On a May day downtown in 1981, he met Lee Standifer

Standifer, born with mild brain damage, was learning to live on her own at age 23. She worked at a food-processing plant, stayed in a room at the YWCA on Clinch Avenue and called home every day to talk to her mother.

Just before her death, she told her mother she felt like she’d just started to live.