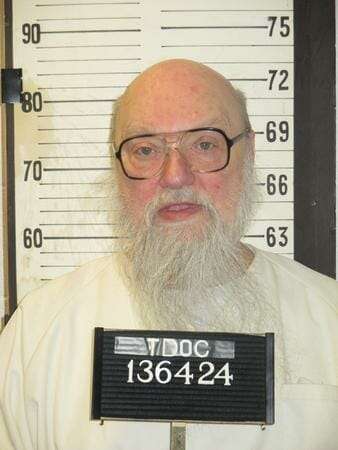

Oscar Smith Execution Scheduled For 5/22/2025

The State of Tennessee is getting set to execute Oscar Smith tomorrow, May 22 2025, for a triple murder According to court documents Oscar Smith would murder his estranged wife Judith Smith, and her sons, Jason and Chad, 13 and 16. Police would arrive at the scene shortly after the triple murders however they found … Read more