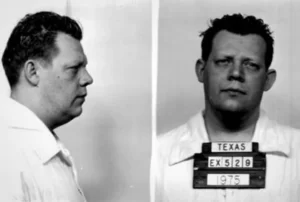

Ronald O’Bryan was executed by the State of Texas for the murder of his son. According to court documents Ronald O’Bryan would take out a large life insurance policy on his son and waited for Halloween. On Halloween Ronald O’Bryan son would die after eating a candy that was laced with poison. Soon police would figure out that Ronald O’Bryan was responsible and he would be arrested, convicted and sentenced to death. Ronald O’Bryan would be executed on March 31, 1984 by lethal injection.

Ronald O’Bryan More News

They say a little rain never hurt anyone. So, when it started drizzling on the night of Halloween 1974, Ronald Clark O’Bryan decided he’d still take his children trick-or-treating. The family only ventured into a few neighborhoods before heading home. Tragically, by the end of the night, O’Bryan’s 8-year-old son, Timothy, would be more than hurt. At bedtime, the boy collapsed from unbearable stomach pain and, on the way to the hospital, died. Authorities determined that he had ingested cyanide-laced candy. Days later, they arrested O’Bryan for the murder of his son.

A&E True Crime explores a case that rattled the nation—and the legacy of the man who killed Halloween.

A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing

Ronald Clark O’Bryan lived with his wife Daynene and two children, Timothy and Elizabeth, in Deer Park, Texas, a middle-class suburb of Houston. He worked as an optician and served as a deacon at a Baptist church, where he sang in the choir and oversaw the parochial bus program. Those who knew O’Bryan considered him a model citizen. One pastor described O’Bryan as “a good, Christian man and an above-average father.”

In reality, O’Bryan had difficulty holding down a job. He was employed by 21 different companies over a 10-year period and fired from each for negligence or fraudulent behavior. In the fall of 1974, 30-year-old O’Bryan was on the brink of being fired again after his employer, Texas State Optical, suspected him of stealing money. His take-home salary of $150 a week barely covered food and rent, and it was later discovered that he was more than $100,000 in debt. He had defaulted on several bank loans and his car was on the verge of being repossessed.

Whether out of greed or desperation, or both, O’Bryan concocted a twisted plan, one that would alleviate his financial woes and even allow him to live a more “comfortable” life. He’d carry it out on Halloween 1974.

An Evil Far Scarier Than Ghosts and Goblins

October 31, 1974 began like any other Halloween night. Although O’Bryan had never shown a real interest in Halloween before, this year he was eager to take his children trick-or-treating. Jim Bates, a family friend, and his two children joined the O’Bryan family for the evening excursion.

At one house, the children went to the door but received no response. O’Bryan remained behind the group. After a minute or so, he caught up with them holding five giant Pixy Stix—a sweet and sour powdered candy that came in a straw-like tube—claiming that the neighbors were actually home and handing out expensive treats. When they arrived back at the Bates’ house, O’Bryan gave each of the four children one candy and then handed the last one to a random trick-or-treater who knocked on his door.

Before bed, O’Bryan told his children they could have one piece of candy. Timothy decided on the Pixy Stix. The boy complained that the candy tasted bitter, so O’Bryan gave him Kool-Aid to help wash it down. “Thirty seconds after I left Tim’s room, I heard him cry to me, ‘Daddy, daddy, my stomach hurts,’” O’Bryan later told police. “He was in the bathroom convulsing, vomiting and gasping and then he suddenly went limp.” Timothy died en route to the hospital less than an hour after eating the candy.

When Timothy’s body was brought to the morgue, the medical examiner recalled the scent of almonds coming from the boy’s mouth, often a telltale sign of cyanide poisoning. An autopsy later confirmed that Timothy had consumed enough potassium cyanide to kill two or three grown men. Police were able to retrieve the other four Pixy Stix—all of which were uneaten—and determined that someone had replaced the top two inches of each with granules of cyanide.

Investigators had O’Bryan and Bates retrace their steps from Halloween night. O’Bryan gave conflicting accounts as to which house handed out the poisoned candy. They soon learned about O’Bryan’s financial problems and discovered he had taken out multiple life insurance policies on his children. They also found a piece of adding machine tape. On it, O’Bryan had written down the amount of each of his bills. The total came to almost the exact amount he stood to collect from the insurance proceeds.

As police dug deeper, they also learned that O’Bryan had inquired with several chemical companies on where to buy cyanide and jokingly asked how much it would take to kill a person. They found a pocketknife in O’Bryan’s home with candy residue on it, suggesting how the candy might have been contaminated. Although O’Bryan played the part of a grieving father and maintained his innocence, after failing a polygraph, he was arrested on November 5, 1974 and charged with Timothy’s murder.

“I am not able to imagine a crime more reprehensible than someone killing his own child for money,” Clyde DeWitt, a former assistant district attorney in Houston who worked on the case, tells A&E True Crime.

Ronald Clark O’ Bryan’s Conviction and Appeals

According to Joni Johnston, a forensic psychologist and private investigator, poisoners as a group typically lack empathy, evidenced by the premeditated nature in which they kill, and the cold, calculating strategy they often use. “[Poisoning] is also an instrument for someone who is kind of cunning and sneaky, not somebody who is going to be physically or verbally aggressive. They are also more likely to be polite behind the scenes and, as a result, they tend to fool people,” Johnston tells A&E True Crime.

But O’Bryan’s days of fooling people were over. On June 3, 1975, after less than an hour of deliberations, a Harris County jury convicted O’Bryan of murder and sentenced him to death.

After being found guilty, O’Bryan appealed his case multiple times, twice to the Supreme Court. “Back then, the constitutional issues surrounding the death penalty were far less settled than is the case now. O’Bryan’s attorney had quite a bit to work with,” says DeWitt.

DeWitt wrote the brief for O’Bryan’s final appeal in 1979. “The facts were extensive and horrible. As I recall, the last sentence of my oral argument to the Court of Criminal Appeals was something like, ‘If these facts do not support the jury’s death sentence, there never will be facts that will,’” says Dewitt, who says he has since developed misgivings about the death penalty.

In the end, all appeals were denied, and O’Bryan was executed by lethal injection on March 31, 1984 at the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville. “What is about to transpire in a few moments is wrong… I would forgive all who have taken part in any way in my death,” O’Bryan’s last words read.

Ronald Clark O’Bryan’s Haunting Legacy

O’Bryan, now known by the nicknames “The Man Who Killed Halloween” and “The Candy Man,” never confessed to his crimes, but there are theories as to why he chose Halloween and poisoned candy to carry out his murder.

“It’s thought that he was aware of the urban legends about Halloween poisoners, and cynically assumed that his use of cyanide-laced candy would deflect suspicion from him to some anonymous boogeyman,” David Skal, a cultural expert on Halloween and author of Fright Favorites: 31 Movies to Haunt Your Halloween and Beyond, tells A&E True Crime.

Nearly 50 years later, O’Bryan’s legacy continues to haunt those familiar with the case. “I spent a month of my life working on it,” says DeWitt. “It is burned into my brain, as you might imagine.”

In a 2004 interview, former Harris County Assistant District Attorney Mike Hinton said, “[O’Bryan is] the man that ruined Halloween for the whole world.”

Skal says that despite O’Bryan’s horrific crime, Halloween shouldn’t be feared. “There is no general correlation in America between the holiday and increased crime. In particular, the widespread fear of poisoned or booby-trapped candy is an urban legend without a real basis.”