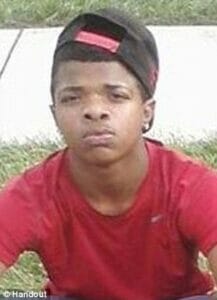

Justin Robinson was fifteen years old when he lured a 12 year old girl to his garage and murdered her. According to court documents Justin Robinson and the 12 year old girl Autumn Pasquale were familiar with each other. On the day of the murder Justin Robinson lured Autumn Pasquale to his garage where the 12 year old was beaten to death. Justin Robinson seventeen year old brother Dante Robinson would be arrested for helping his brother hide up the problem. This teen killer would be arrested, convicted and sentenced to seventeen years in prison with the first fourteen year old being mandatory

Justin Robinson 2023 Information

| Justin M Robinson | |

| SBI Number: | 000897557E |

| Sentenced as: | Robinson, Justin M |

| Race: | Black |

| Ethnicity: | Unknown |

| Sex: | Male |

| Hair Color: | Black |

| Eye Color: | Brown |

| Height: | 6’0″ |

| Weight: | 210 lbs. |

| Birth Date: | March 1, 1997 |

| Admission Date: | September 12, 2013 |

| Current Facility: | GYCF |

| Current Max Release Date: | April 4, 2027 |

| Current Parole Eligibility Date: | April 4, 2027 |

Justin Robinson More News

ust about everyone in New Jersey has heard about what happened to Autumn Pasquale, a spunky 12-year-old with a sprinkle of freckles and brilliant blonde hair.

They’ve heard how she climbed on her white BMX bike on a Saturday afternoon nearly 5 1/2 years ago, pedaled away from her High Street home and disappeared. Thousands in the small borough of Clayton and nearby towns searched backyards and fields, only to find her body two days later crumpled in a blue recycling container in front of a vacant home.

Less than 72 hours after Autumn was last seen, police announced the arrests of two teenage brothers, 15-year-old Justin and 17-year-old Dante Robinson. Prosecutors said the brothers lured Autumn to their home across town and killed her in a scheme to steal parts from her bike. In the waning days of 2012, the tragic story from this small corner of the state was bandied across the nation as a cautionary tale.

For the first time since 2013, when Justin Robinson was sentenced to 17 years in prison in her killing, both Robinson and his mother, Anita Saunders, have agreed to talk publicly about what happened the day Autumn died. Separately, they sat down with NJ Advance Media to tell their side of the story.

While Autumn’s family and many others believe the crime was simply a cold-blooded killing, Robinson insists the story reported for five years is a distortion of what really happened.

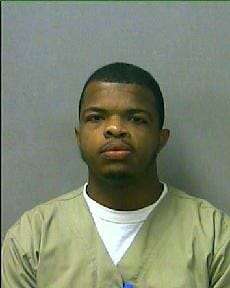

Justin Robinson sits at a table in a small meeting room at Garden State Youth Correctional Facility in Chesterfield, Burlington County, where he’s been for the past 4 1/2 years and will likely be until at least 2027.

He pleaded guilty to aggravated manslaughter, after initially being charged with murder. His brother Dante, also charged with murder, admitted to fourth-degree obstruction, and was jailed for 11 months.

Dressed in a beige prison uniform, the now 21-year-old spoke calmly for about 40 minutes about what happened in 2012.

Justin Robinson doesn’t deny strangling Autumn in his parents’ basement on Saturday, Oct. 20, 2012, and then hiding her body.

“I’m deeply sorry,” Robinson says. “I didn’t really want this to happen. If I could take it back I would.” But, he says, “I didn’t kill her for no bike.”

Autumn, he says, wasn’t a stranger. The high school freshman knew her older sibling and he would see Autumn, a seventh-grader, at school. Both Clayton Middle and High School share the same campus. “We used to talk in the hallways.”

Autumn was an outgoing, straight-A student and a tomboy. She loved her BMX bike and playing soccer. She was a dancer and cheerleader before soccer and softball drew her attention.

When she posted on Facebook about needing someone to install new rims on her bike, Robinson said he offered to help. On a Friday night, the two made small talk on Facebook messenger for about two hours.

“Can u put my stuff on mh bike tmw pls,” she asks.

“K can u meet me somwhere close cause i cant really walk tht well,” he responds. He had a childhood ankle injury that sometimes made it difficult to get around, his mother explained.

At another point in the conversation, he asked Autumn if she was single. “Ya,” she replies. He told her he thought she was attractive.

Autumn Pasquale and Justin Robinson communicated via Facebook the night before her death.

Breaking the rules

Robinson knew his mother and stepfather, Richard Saunders, were going to be a few blocks away Saturday afternoon, at the high school where one of his five brothers was playing in the Homecoming football game.

And he knew his mother had a strict rule for her boys: No girls in the house when their parents were away. But he broke that rule.

Autumn’s final message to Robinson came shortly before 3 p.m. Saturday. She had biked the half mile from her home to his street and was trying to find his house. “K ill b there just stay there,” she wrote.

Saunders shared those messages with NJ Advance Media, which she said were part of discovery in the case against her son. The messages show two kids planning to meet up, not the prelude to a premeditated crime, she said.

In the basement of his house, Robinson said Autumn offered him $10 to install the rims.

After he was finished with her bicycle, he asked for the money. She said she didn’t have it with her.

Autumn Pasquale died in the Robinson home on East Clayton Avenue. (File photo)

“You can’t get the bike unless you give me the money,” Robinson recalled telling her.

But she had no plans of leaving without her bike and Autumn began hitting him, Robinson claims.

“I didn’t know what to do,” he says. “I didn’t want to hit her physically. I just threw my hands around her neck and I just choked her until she stopped hitting me. When she went limp, I let her go.”

She died, investigators said, from “blunt force trauma, consistent with strangulation.”

s Autumn’s lifeless body lay on the basement floor, Robinson said he went into a “frantic panic mode” as he tried to figure out what to do next.

“A lot of people thought I planned it,” he says. “There was nothing planned about this. There was never no intention to lure her or kill her for her bike. No traps. Nothing.”

His tone remains calm and focused as he explains his next actions.

Robinson thought about how to get her body out of the basement.

“At first I got a trash bag and that didn’t really work,” he said.

Then, he went to the vacant house next door and retrieved the recycling container. He struggled to bring her body up from the basement and some of her clothing came off as he pulled her up the stairs, he said. Investigators later found the clothing in a trash bag in the family’s kitchen.

Robinson dropped her body in the recycling container and wheeled it back to the neighbor’s house.

When his parents returned home around 4 p.m., his mother asked him why he was sweating. Robinson assured her that everything was fine.

In reality, he said he felt like he was caught in a bad dream.

“I was just really numb,” he said. “I was really just trying to wake up.”

In an apparent effort to cover his tracks, Robinson sent another Facebook message to Autumn that night, “Just got home sorry tomrow,” following by a later message saying “hey wassup.”

Autumn’s father, Anthony Pasquale, reported her missing around 9:30 p.m. Saturday. In the two days that followed, her family, friends and complete strangers mobilized a massive community search for a girl in a yellow T-shirt, navy sweatpants and bright blue high-top sneakers.

State Police flew helicopters, K-9 units were brought in and school kids handed out fliers.

After investigators learned that Justin Robinson was the last person in contact with Autumn before she disappeared, police visited the Robinson home. Robinson told them he only spoke with her outside, according to one investigation report. Then he denied she had been there at all.

Based on his shifting stories, detectives asked both Justin and Dante, their mother and stepfather to come to the police station for an interview on the evening of Monday, Oct. 22

That night, while the Robinson family was being interviewed, police found Autumn’s body.

When Justin and Dante learned this, they “became upset and angry,” according to an investigator’s statement.

A patrolman on duty said he prayed with Justin in the station’s processing room. During their prayer, “Justin asked if Jesus would forgive him, and told them he strangled Pasquale in the basement of his residence,” according to the police report.

Dante was upstairs in his room listening to music when Autumn was killed, Saunders said.

He told investigators he heard Autumn scream, but “I didn’t think nothing of it.”

Apparently unaware of what happened in the basement, Dante said he yelled from his room to “hurry up and get that girl out of here before mommy got home.” Dante saw his brother a short time later and asked him if she had left. He said she had.

An investigator’s report describes the moment Justin Robinson confessed to the killing.

Dante later pleaded guilty to obstruction, was sentenced to six months and released on time served in 2013. The obstruction charge stemmed from Dante supposedly blocking investigators from seeing that Autumn’s bike was in the house, Saunders said, but she denied that he had done this.

“Dante did 11 months for something he didn’t do,” she said.

Saunders insists Autumn’s death was an “accident.”

“Something went wrong between two kids,” she said. “It was a genuine accident that wasn’t planned. … She was not leaving her bike. You had two kids and they’re both trying to stand their ground.”

None of the prosecutors in Gloucester County or Camden County, where the case was later transferred, would talk about the Robinson family’s claims.

The Clayton community grieved Autumn’s death publicly. Thousands attended her funeral and various memorial events. A scholarship was established in Autumn’s memory and a memorial park on East Avenue was dedicated in her honor.

There was an inverse response by the community to the Robinsons. In the hours after their arrest, rumors spread swiftly. Some claimed Autumn was raped, even though investigators found no evidence of a sexual assault.

There were rumors that Justin Robinson was laughing at a vigil for Autumn, even though the brothers were already at the police station the night the vigil was held.

The boys’ own father, Alonzo Robinson, told the Star-Ledger after the arrests that his sons were known bike thieves. Robinson was estranged from his kids and ex-wife.

It wasn’t true, Justin Robinson said. His mom had bought him a $500 Subrosa BMX-style stunt bike for his birthday, so he says he had no need to take from others.

When announcing the brothers’ arrests, prosecutors said their mother had contacted police to say she found something suspicious on one of their Facebook pages that led her to think they may be involved. Saunders denies this ever happened.

Autumn’s father, a postal worker who at one time delivered mail to the Robinson family’s bungalow-style home on East Clayton Avenue, has long argued that the parents of his daughter’s killer knew that their son was prone to violence and that he had witnessed domestic violence in the home.

He said the arrest last May of Dante Robinson for his alleged involvement in a violent home invasion in Gloucester Township further proved his point.

Anthony Pasquale sought legislation — called Autumn’s Law — that would hold parents criminally responsible when their kids commit violent crimes. The bill hasn’t received legislative support.

As the current school year began, Pasquale reflected on the fact that this would have been Autumn’s senior year in high school. “I can’t believe it’s been five years,” he said at the time.

He didn’t have much to say after being told about the Robinson family’s recent comments. “They know how I feel,” he said.

Saunders said the prosecution of her son’s case and ongoing litigation prevented her from speaking out publicly at the time.

“I was told that I could not talk because we were not sure if he was going to go to trial,” she said. “After a couple of years, I felt like it is what it is. I cannot bring Autumn back. I cannot bring my son back from prison.”

Criticism of her family and what she describes as lies about her son’s mental status forced her to finally speak up, she said.

Saunders and Justin Robinson dispute the idea that anything that happened in the house before Saunders divorced the brothers’ father in 2006 would lead the kids to be violent.

“None of my kids have any kind of learned behavior to where they could do harm to people,” Saunders, a funeral director, says. “I took a strong resentment to that.”

Robinson denies that he has any disorder, despite his public defender’s revelation in a 2013 hearing that he was diagnosed with a neurodevelopmental disorder, intellectual disabilities, low-IQ, post-traumatic stress disorder and attention deficit disorder.

Saunders also denied claims that her son suffered from fetal alcohol syndrome.

Before Autumn’s murder, Saunders says she believed everyone in Clayton, a town that’s about 70 percent white, got along. After Autumn’s death, her perceptions about the town of 8,000 changed.

She said people drove past their home yelling racial epithets and throwing trash in her yard, and talked on social media about burning down her house and killing her family.

“Everybody made it a racial thing,” she said.

Others wanted to buy the family’s home from the borough, Saunders said. “They just assumed that I was behind on my taxes,” she said, adding that she wasn’t.

‘I pray for Autumn’

During Saunders’ regular visits to see her son in prison, she says she has seen him mature. Religion has played a big part in that process, she said.

“He told me, ‘Mom, I pray for Autumn,'” she said. “He even prays for her family. That just knocked me off my feet to hear him say that.”

Religion, he says, is also the reason why he stopped participating in any psychological care in prison. This care was directed as part of his sentencing.

“I didn’t need anymore,” he says. “I got deep in my religion. It opened my eyes a lot … it brings me peace.”

When he looks to the future, Robinson speaks about attending college and pursuing a career. He’ll be 30 by the time he’s eligible for parole, according to Department of Corrections records.

He doesn’t, however, plan to return to Clayton. “There’s really nothing for me there anymore,” he said.

Before returning to his cell, Robinson asks for forgiveness and insists he’s not a “stone-cold murderer.”

“It was an honest mistake. I’m being punished for it,” Robinson said. “I hope they can just forgive me. It’s hard to forgive a person when they take one of your loved one’s life. I want them to know that I really am sorry.”

https://www.nj.com/news/2018/03/a_killer_explains_slaying_of_a_child_i_didnt_kill.html

Justin Robinson FAQ

Justin Robinson Now

Justin Robinson is currently incarcerated at the Garden State Youth Correctional Facility

Justin Robinson Release Date

Justin Robinson is scheduled for release in 2037