Benny Hodge was sentenced to death by the State of Kentucky for the murder of a woman during a robbery. According to court documents Benny Hodge and Roger Epperson entered a home in Kentucky. Once inside they choked a male occupant unconscious before stabbing the man’s daughter to death. Benny Hodge and Roger Epperson were both arrested, convicted and sentenced to death. Roger Epperson is currently going through a resentencing and is no longer listed as being on Kentucky’s death row

Kentucky Death Row Inmate List

Benny Hodge 2021 Information

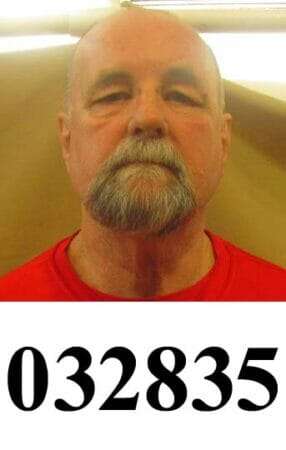

| Name: | HODGE, BENNY LEE Active Inmate DEATH ROW | Offender Photo(Click image to enlarge) | |

| PID # / DOC #: | 215174 / 032835 | ||

| Institution Start Date: | 6/21/1986 | ||

| Expected Time To Serve (TTS): | DEATH SENTENCE | ||

| Classification: | Maximum | ||

| Minimum Expiration of Sentence Date (Good Time Release Date): ? | DEATH SENTENCE | ||

| Parole Eligibility Date: | DEATH SENTENCE | ||

| Maximum Expiration of Sentence Date: | DEATH SENTENCE | ||

| Location: | Kentucky State Penitentiary | ||

| Age: | 69 | ||

| Race: | White | ||

| Gender: | M | ||

| Eye Color: | Hazel | ||

| Hair Color: | Brown | ||

| Height: | 6′ 1 “ | ||

| Weight: | 205 |

Benny Hodge More News

Hodge was sentenced to death on June 20, 1986 in Letcher County along with Roger Epperson for the murder of Tammy Acker. The murder occurred when Hodge and two accomplices entered the home of a Fleming-Neon, Kentucky physician on the night of August 8, 1985. They choked the man unconscious, and stabbed his daughter, Tammy Acker, to death while robbing him of $1.9 million, handguns, and jewelry. He was arrested in Florida on August 15, 1985. He also received a second death sentence on November 22, 1996 for the murder and robbery of Bessie and Edwin Morris in their home in Gray Hawk, Kentucky on June 16, 1985.

Benny Hodge Other News

Hodge and two others posed as Federal Bureau of Investigation agents to gain entry to the home of a doctor. Once inside, they strangled the doctor into unconsciousness, stabbed his college-aged daughter to death, and stole around $2 million in cash, as well as jewelry and guns, from a safe. A jury convicted Hodge and a codefendant of murder and related charges. Epperson v. Commonwealth, 809 S. W. 2d 835, 837 (Ky. 1990). In advance of the penalty phase of his trial, Hodge’s counsel conducted no investigation into potential mitigation evidence and presented no evidence to the jury. The Commonwealth did not put on evidence of aggravating circumstances either, beyond the facts of the crime. Instead, the parties agreed that the jury should be read this stipulation: ” ‘Benny Lee Hodge has a loving and supportive family–a wife and three children. He has a public job work record and he lives and resides permanently in Tennessee.’ ” App. to Pet. for Cert. 5. After hearing argument from counsel on both sides, the jury recommended a sentence of death, which the trial court imposed.

On postconviction review in Kentucky state court, Hodge alleged that his counsel had been ineffective during the penalty phase for failing to investigate, discover, and present readily available mitigation evidence concerning his childhood, which was marked by extreme abuse. Hodge was granted an evidentiary hearing, during which he presented extensive mitigation evidence and the testimony of expert psychologists. The Commonwealth did not contest Hodge’s evidence, although it did not concede that all the evidence would have been available or admissible at the time of trial. The Kentucky Supreme Court credited the evidence and found it would have been available at the time of trial. The evidence established the following:

The beatings began in utero. Hodge’s father battered his mother while she carried Hodge in her womb, and continued to beat her once Hodge was born, even while she held the infant in her arms. When Hodge was a few years older, he escaped his mother’s next husband, a drunkard, by staying with his stepfather’s parents, bootleggers who ran a brothel. His mother next married Billy Joe. Family members described Billy Joe as a ” ‘monster.’ ” Id., at 7. Billy Joe controlled what little money the family had, leaving them to live in abject poverty. He beat Hodge’s mother relentlessly, once so severely that she had a miscarriage. He raped her regularly. And he threatened to kill her while pointing a gun at her. All of this abuse occurred while Hodge and his sisters could see or hear. And following many beatings, Hodge and his sisters thought their mother was dead.

Billy Joe also targeted Hodge’s sisters, molesting at least one of them. But according to neighbors and family members, as the only male in the house, Hodge bore the brunt of Billy Joe’s anger, especially when he tried to defend his mother and sisters from attack. Billy Joe often beat Hodge with a belt, sometimes leaving imprints from his belt buckle on Hodge’s body. Hodge was kicked, thrown against walls, and punched. Billy Joe once made Hodge watch while he brutally killed Hodge’s dog. On another occasion, Billy Joe rubbed Hodge’s nose in his own feces.

The abuse took its toll on Hodge. He had been an average student in school, but he began to change when Billy Joe entered his life. He started stealing around age 12, and wound up in juvenile detention for his crimes. There, Hodge was beaten routinely and subjected to frequent verbal and emotional abuse. After assaulting Billy Joe at age 16, Hodge returned to juvenile detention, where the abuse continued. Hodge remained there until he was 18. Over the 16 years between his release from juvenile detention and the murder, Hodge committed various theft crimes that landed him in prison for about 13 of those years. He twice escaped, but each time, he was recaptured.

Psychologists who testified at Hodge’s evidentiary hearing, and were credited by the court below, explained that the degree of domestic violence Hodge suffered was extremely damaging to his development. The environment caused ” ‘hypervigilance’ “–a state of constant anxiety that left Hodge always ” ‘waiting for the next shoe to fall.’ ” Pet. for Cert. 7. It taught him ” ‘that the world was a hostile place and that he was not going to be able to count on anybody else to protect him’ “–not his family and not society. Id., at 8. Being taken to a juvenile facility only to be beaten more likely hit Hodge as a ” ‘double betrayal.’ ” Id., at 9. The result was that Hodge had posttraumatic stress disorder. Unable to control his behavior and his emotions because of PTSD, he turned to drugs and alcohol to numb his feelings. This condition could have been diagnosed at the time of his trial.

The Commonwealth conceded that counsel was deficient for failing to gather and present this evidence at the penalty phase of Hodge’s trial. But it contended that Hodge would have been sentenced to death even if the evidence had been presented. Examining the evidence, the Kentucky Supreme Court had “no doubt that Hodge, as a child, suffered a most severe and unimaginable level of physical and mental abuse.” App. to Pet. for Cert. 11. Yet it felt “compelled to reach the conclusion that there exists no reasonable probability that the jury would not have sentenced Hodge to death” anyway. Ibid.

The Court based its conclusion in part on the aggravating circumstances against which the jury would have had to weigh the mitigation evidence. The murder itself was “calculated and exceedingly cold-hearted.” Id., at 9. Hodge stabbed the daughter “at least ten times,” and he “coolly” told his codefendant that he knew the daughter “was dead because the knife had gone ‘all the way through her to the floor.’ ” Id., at 10. Hodge’s conduct after the murder was shocking as well: He and the two other robbers “brazenly spent the stolen money on a lavish lifestyle and luxury goods, including a Corvette,” and Hodge told a cellmate he had “sprea[d] all the money out on a bed and ha[d] sex with his girlfriend on top of it.” Ibid. Moreover, had Hodge put on evidence in mitigation, the Commonwealth may have sought to introduce evidence of Hodge’s “long and increasingly violent criminal history, his numerous escapes from custody, and the obvious failure of several rehabilitative efforts.” Id., at 9.