Billy Coble was executed by the State of Texas for a triple murder. According to court documents Billy Coble would murder his estranged wife’s parents and brother. Billy Coble would be executed by lethal injection on March 1, 2019.

Billy Coble More News

A Texas inmate was executed Thursday evening for the killings nearly 30 years ago of his estranged wife’s parents and her brother, who was a police officer.

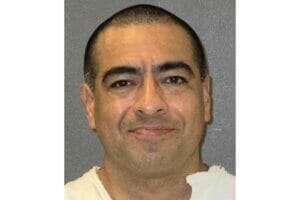

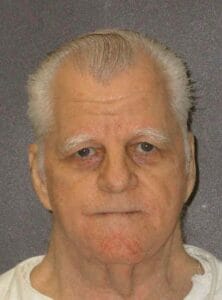

Billie Wayne Coble received lethal injection at the state penitentiary in Huntsville for the August 1989 shooting deaths of Robert and Zelda Vicha and their son, Bobby Vicha, at separate homes in Axtell, northeast of Waco.

Coble, 70, once described by a prosecutor as having “a heart full of scorpions,” was the oldest inmate executed by Texas since the state resumed carrying out capital punishment in 1982.

Asked to make a final statement, Coble replied: “That’ll be $5.”

He told the five witnesses he selected to be in attendance that he loved them, then again said: “That’ll be $5.” Coble nodded to the witnesses and added, “take care.”

He gasped several times and began snoring.

As Coble was finishing his statement, his son, a friend and a daughter-in-law became emotional and violent. They were yelling obscenities, throwing fists and kicking at others in the death chamber witness area.

Officers stepped in and the witnesses continued to resist. They were eventually moved to a courtyard and the two men were handcuffed.

“Why are you doing this?” the woman asked. “They just killed his daddy.”

While the witnesses were being subdued outside, the single dose of pentobarbital was being administered to Coble. He was pronounced dead 11 minutes later at 6:24 p.m.

Texas Department of Criminal Justice spokesman Jeremy Desel said the two men were arrested on a charge of resisting arrest and taken to the Walker County Jail.

The U.S. Supreme Court earlier Thursday turned down Coble’s request to delay his execution.

His attorneys had told the high court that Coble’s original trial lawyers were negligent for conceding his guilt by failing to present an insanity defense before a jury convicted him of capital murder.

A state appeals court had previously rejected Coble’s request to delay Thursday’s execution and the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles turned down his request for a commutation.

Coble “does not deny that he bears responsibility for the victims’ loss of life, but he nonetheless wanted his lawyers to present a defense on his behalf,” his attorney, A. Richard Ellis, said in his appeal to the Supreme Court.

In Coble’s clemency petition to the Board of Pardons and Paroles, Ellis said his client suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder stemming from his time as a Marine during the Vietnam War and was convicted, in part, due to misleading testimony from two prosecution expert witnesses on whether he would be a future danger.

Billy Coble was the third inmate put to death this year in the U.S. and the second in Texas, the nation’s busiest capital punishment state.

“This is not a happy night,” McLennan County District Attorney Barry Johnson said. “This is the end of a horror story for the Vicha family.”

J.R. Vicha, Bobby Vicha’s son, said it would be a relief knowing the execution finally took place after years of delays.

“Still, the way they do it is more humane than what he did to my family. It’s not what he deserves but it will be good to know we got as much justice as allowed by the law,” said J.R. Vicha, who was 11 when he was tied up and threatened by Coble during the killings.

Prosecutors said Billy Coble, distraught over his pending divorce, kidnapped his wife, Karen Vicha. He was arrested and later freed on bond.

Nine days after the kidnapping, Billy Coble went to Karen Vicha’s home, where he handcuffed and tied up her three daughters and J.R. Vicha. He then went to the homes of Robert and Zelda Vicha, 64 and 60 respectively, and Bobby Vicha, 39, who lived nearby, and fatally shot them. After Karen Vicha returned home, Coble abducted her and drove off, assaulting her and threatening to rape and kill her. He was arrested after wrecking in neighboring Bosque County following a police chase.

Billy Coble was convicted of capital murder in 1990. In 2007, the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ordered a new trial on punishment. On retrial in 2008, a second jury sentenced him to death.

Crawford Long, the former first assistant district attorney in McLennan County who helped retry Coble in 2008, said his “heart full of scorpions” description of Coble was fitting.

“He had no remorse at all,” said Long, who retired in 2010.

J.R. Vicha, 40, still lives in the Waco area. He eventually became a prosecutor for eight years, a career choice inspired in part by his father, who was a police sergeant in Waco when he was killed. His grandfather was a retired plumber and his grandmother worked for a foot doctor.

Vicha, now a private practice lawyer, is working to get a portion of a highway near his home renamed in honor of his father.

“Every time I run into somebody that knew (his father and grandparents), it’s a good feeling. And when I hear stories about them, it still makes it feel like they’re kinda still here,” Vicha said.