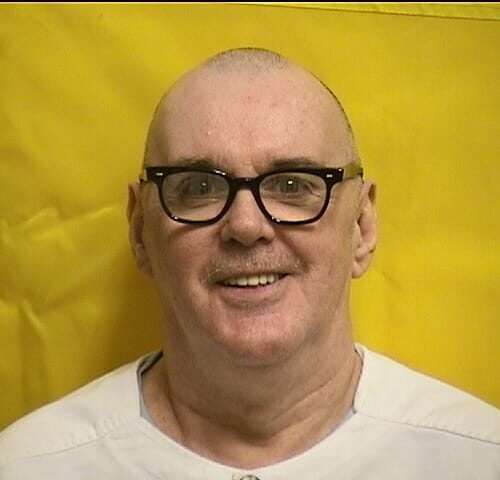

Douglas Coley was sentenced to death by the State of Ohio for a carjacking that ended in a murder. According to court documents Douglas Coley would drag the victim, Samar El-Okdi , from her car to an alley where she was fatally shot and Douglas Coley would then steal her car. Douglas Coley would be arrested, convicted and sentenced to death.

Ohio Death Row Inmate List

Douglas Coley 2021 Information

Number A361444

DOB 08/24/1975

Gender Male Race Black

Admission Date 06/16/1998

Institution Chillicothe Correctional Institution

Status INCARCERATED

Douglas Coley More News

On December 23, 1996, around 7:30 p.m., David Moore parked his light blue, four-door Ford Taurus at his residence in Toledo. While Moore was unloading his car trunk, a man he later identified as Green asked for directions. As he gave directions, another man appeared, whom Moore later identified as Coley. Moore started to leave, but Green and Coley stood in front of him and displayed small-caliber, shiny, semiautomatic pistols. Coley then told Moore, “Give me your keys.” Moore complied, and Coley told Moore, “Get in the car.” Coley then climbed in behind the wheel, Green got in back behind Moore, and Coley drove the Taurus towards the art museum.

While in the car, Moore asked them to let him go, but neither Green nor Coley responded. Green did tell Moore to “cough up the cash,” and Moore handed Coley $112, which Coley threw on the front seat. Moore noted that Coley was calm and never appeared excited, aggravated, confused, or unsure of himself. After approximately fifteen minutes, Coley pulled into a dark, isolated field and told Moore to get out of the car.

As Moore backed out of the car, Coley shot him in the stomach. After Moore ran away, he heard a car door open and the car wheels spinning, “trying to get out of the mud.” Moore heard somebody chasing him. Other shots were fired, and Moore fell down. Then Moore heard another shot and felt a bullet hit him in the head. He pretended that he was dead, but as his assailant walked away, Moore looked back and thought that Green, who was heavier and taller than Coley, was the one who had just shot him.

Eventually, Moore struggled to his feet, went to a nearby house, and summoned assistance. Police and a medical team responded and took Moore to a hospital. Moore had been shot in the head, stomach, and arms, and twice in the hand. During one operation, a surgeon removed a .25 caliber bullet from Moore’s wrist.

In addition to the bullet from Moore’s wrist, police found two .25 caliber shell casings on Green Street near where Moore had been shot. Evidence established that a gun identified as Coley’s gun had ejected the shell casings found on Green Street and fired the bullet removed from Moore’s wrist.

On an evening shortly before Christmas 1996, Tyrone Armstrong, a cousin of both Coley and Green, saw Coley and Green driving a light blue, four-door Ford Taurus. The Taurus, which Armstrong knew did not belong to either of them, was overheating, so Armstrong helped put water in the car. Before his abduction, Moore had purchased but not installed a new replacement radiator because his Taurus tended to overheat.

That same evening, Armstrong saw Coley and Green with the same .25 caliber semiautomatic pistols that Armstrong had seen each of them previously carry. Armstrong identified State Exhibit 32, a brown-handled pistol with gray duct tape, as the weapon Coley had previously carried, and State Exhibit 33, which had a pearl handle, as Green’s pistol. That evening, Green made up a rap song with the words “I shot him five times and he had dropped.” At one point, Green pointed his gun at Coley and said, “You better never snitch on me.” Coley mimicked the action; pointing his gun at Green, and repeating, “Better never snitch on me.” Penne Graves, Coley’s girlfriend, also recognized State Exhibit 32 as a gun she had seen around her house.

After a few days, Coley and Green abandoned Moore’s Taurus. On December 27, 1996, police recovered Moore’s car in an area near the residence of a girlfriend of Coley. When police found the Taurus, it bore plates that had been stolen from a Mercury Topaz.

Murder of Samar El-Okdi

Samar El-Okdi was found dead in an alley on January 7, 1997. She had last been seen on January 3, 1997. The police traced El-Okdi’s movements on Friday, January 3, 1997, from around 5:00 p.m. until 8:00 p.m., but no evidence firmly established exactly where or when she had been abducted. Sometime after 5:00 p.m. that day, El-Okdi left work and told coworkers that she planned to spend the evening at home. She drove her Pontiac 6000 to her apartment, a block from Moore’s residence. Raymond Sunderman, her landlord, saw El-Okdi arrive home sometime between 5:00 and 5:30 p.m. El-Okdi’s brother, Samir El-Okdi, recalls that El-Okdi stopped by late that afternoon at the family-owned convenience store for thirty to forty-five minutes. Around 8:00 p.m., El-Okdi dropped film off at the Blue Ribbon Photo store at Westgate Shopping Center.

That same Friday, around 8:45 p.m., Rosie Frusher left a friend’s house at West Grove Place, near the Toledo Art Museum, to use a pay telephone. As Frusher walked outside the house at which she was staying, she heard two gunshots. After she had passed by the house, she saw a car to her left in an alley. The car had “long taillights” (similar to those on a Pontiac 6000) and a license plate number with a zero (unlike El-Okdi’s license number). Frusher saw a black, stocky “man outside the car bending over that had bushy hair.” Another man was sitting in the driver’s seat. Then Frusher walked to the pay phone and talked to her friend for thirty minutes or so, but she did not return the same way she had come earlier. Ameritech records establish that Frusher made this call at 8:41 p.m.

On Saturday, January 4, Christopher Neal, El-Okdi’s boyfriend, discovered that El-Okdi was missing and notified police. El-Okdi’s friends and relatives searched for El-Okdi, hired a private detective, and distributed missing-person flyers. These flyers described El-Okdi, included her photograph, described her car, including the bumper stickers, and listed her last known whereabouts.

That same weekend in Toledo, Armstrong saw Coley driving a gray Pontiac 6000 that he later identified as El-Okdi’s car. On the night his cousins were arrested, Armstrong bought some cigars and two bottles of Alize (an alcoholic beverage) for Green and Coley, which police later found in that Pontiac. Armstrong admitted that Green and Coley had keys and used those keys to drive both the Taurus and the Pontiac.

Later that night, Monday, January 6, Megan Mattimoe, El-Okdi’s friend and coworker, was parked on Scottwood waiting for another friend to distribute the missing-person flyers about El-Okdi. Around 11:15 p.m., Mattimoe saw El-Okdi’s car drive by, which she identified by its dented rear fender and a distinctive bumper sticker, although the license plate was different. While following the Pontiac, Mattimoe used a cellphone to call a friend, who in turn called the police. Mattimoe followed the Pontiac until the driver parked at an apartment complex and two men got out.

After talking with police, Mattimoe and a Toledo detective returned to where the stolen Pontiac was parked. It bore an Ohio license plate, number YRT 022, which had been stolen from another Pontiac 6000 some time before 6:00 p.m. on January 4, 1997. Police staked out the car, using five undercover police vehicles.

After midnight, Green, Coley, and a woman with a baby got into the Pontiac and drove away. Police followed in undercover vehicles and, assisted by marked police cars, forced the Pontiac to stop. Despite being surrounded, Green rammed one car and spun his wheels in an effort to escape. Green and Coley also resisted arrest, and police forcibly removed each of them from the car. Police found a loaded pistol in Green’s coat. When one policeman approached the car, he noticed that Coley, who was sitting in the back seat, had a metallic object in his hand. On the Pontiac’s rear floor, police found a loaded, .25 caliber, brown-handled pistol (Exhibit 32) near where Coley had been sitting.

Inside the trunk, police found a black crochet purse that El-Okdi had with her on January 3 when she disappeared. However, police never found her red wallet and credit cards, which she always carried with her inside the black purse. Police found one of El-Okdi’s license plates underneath the stolen rear plate, and they found her other license plate in the car trunk.

On the afternoon of January 7, police found El-Okdi’s body in an alley behind West Grove Place, where Frusher had heard shots and had seen two men in a car four days earlier. El-Okdi was wearing the same white shirt, black shoes, and black trousers that she wore to work on January 3. At the scene, police found a live .25 caliber bullet and a .25 caliber shell casing near El-Okdi’s body.

The deputy coroner found that El-Okdi had died from a .25 caliber bullet, which the deputy coroner removed from the back of her cerebellum. The bullet had struck her between the eyes and had been fired from a muzzle distance of approximately twelve to eighteen inches. The deputy coroner concluded that El-Okdi did not die immediately.

David Cogan, a firearms expert, examined the .25 caliber bullet removed from El-Okdi’s brain, the .25 caliber bullet removed from Moore’s wrist, three .25 caliber shell casings from the two crime scenes, and Coley’s .25 caliber semiautomatic pistol recovered from the rear floor of El-Okdi’s Pontiac. Cogan concluded that Coley’s pistol was in operating condition and had fired the bullets into Moore and El-Okdi and had ejected the three crime-scene shell casings. After police searched Green’s residence on January 7, 1997, they found an empty box that had contained .25 caliber Remington ammunition.

On January 7, 1997, Coley and Green were arraigned on charges relating to El-Okdi’s stolen Pontiac and the stolen plates. That arraignment was shown on television, and Moore immediately recognized Green and Coley from the television newscast as the men who had kidnapped, robbed, and shot him.

That same week, Coley, Green and their cousin Armstrong were all in jail, although Armstrong was being held on unrelated charges. While Armstrong and Coley were together, Coley hugged him and told him, “I did it but Joe [Green] shouldn’t have snitched on me.” By this comment, Armstrong understood Coley to mean that Coley had shot El-Okdi. Coley also asked Armstrong to lie for him by claiming that Coley had obtained his weapon and the Pontiac from someone named Denny.

On January 16, 1997, a grand jury heard allegations relating to El-Okdi, and returned an indictment of murder, without death-penalty specifications. Coley was reindicted on March 10, 1997, with the grand jury returning an eight-count indictment for the following offenses: Count I, the kidnapping of David Moore, in violation of R.C. 2905.01(A)(2); Count II, the aggravated robbery of David Moore, in violation of R.C. 2911.01(A)(1); Count III, the attempted murder of David Moore, in violation of R.C. 2923.02; Count IV, the aggravated murder of Samar El-Okdi, in violation of R.C. 2903.01(A); Count V, the aggravated murder of Samar El-Okdi, in violation of R.C. 2903.01(B); Count VI, the aggravated murder of Samar El-Okdi, in violation of R.C. 2903.01(B); Count VII, the kidnapping of Samar El-Okdi, in violation of R.C. 2905.01(A)(2); and Count VIII, the aggravated robbery of Samar El-Okdi, in violation of R.C. 2911.01(A)(1). Each count included a firearm specification in violation of R.C. 2941.145. Count III also had a firearm specification under R.C. 2941.146. Each murder count included a specification under R.C. 2929.04(A)(7) that the murder was committed during a kidnapping or robbery.

Coley pleaded not guilty to the charges, and was convicted as charged, and the jury found both that Coley was the principal offender in the aggravated murder and that he committed the offense with prior calculation and design. The trial court later merged the three aggravated murder Counts (IV, V, and VI). After a sentencing hearing, the jury recommended, and the trial judge imposed, a death sentence for the aggravated murder of Samar El-Okdi. In addition to the death sentence, the trial court sentenced Coley to ten years on each of Counts I, II, III, VII, and VIII, to be served consecutively, and sentenced him on the firearm specifications.

https://caselaw.findlaw.com/oh-supreme-court/1467924.html