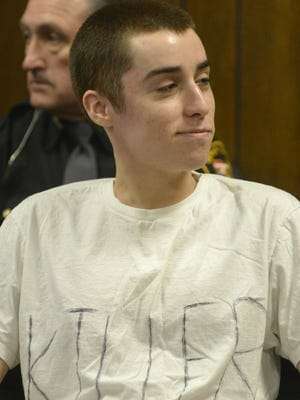

Barry Loukaitis Teen Killer School Shooter

Barry Loukaitis was fifteen years old when he walked into his school and shot dead a teacher and two students. This teen killer would hold his class hostage for over an hour before he was tackled by a teacher. Barry Loukaitis would be convicted on all three of the murders and receive a prison sentence of two life sentences … Read more